I remember [Pickford] telling me that she couldn't bear the way [D. W. Griffith] directed adolescent girls. She said, "Oh, he directed them so they ran around like a chicken with its head cut off. And I would not do that sort of thing..." She already saw that naturalism was terribly important, even more than Griffith did.

Kevin Brownlow

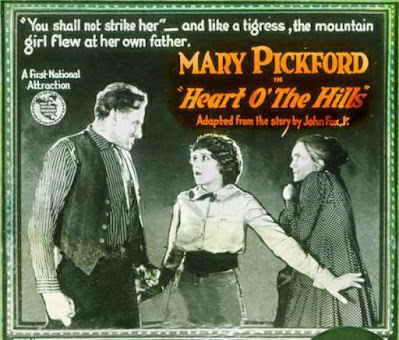

For the first time since the Pandemic, it was time to

play Six Degrees of Kevin Brownlow and, as usual, the answer was two; Kevin had

met and interviewed Mary Pickford on a number of occasions. This direct

relationship with the “source material”, one of the major players, one of the

three of four, who really made the cinema of Hollywood in the 1910s, predating

even Kennington’s own Charlie and her husband Doug, even outshining her director

on so many occasions, David Wark, distancing herself in a way Lillian didn’t as

she set up her own production company in 1918 and took charge of her intellectual

property as well as her career.

Kevin’s introduction focused on fellow film collector Bert

Langdon and his own meetings with Heart o' the Hills’ cinematographer, Londoner

Charles Rosher, who shot all of Pickford’s films from 1918 to 1927, became the

first cameraman to win an Oscar for Sunrise and grabbed a second for The

Yearling (1946). Kevin’s friend was able to screen his original 35m nitrate

original not just of this film but also My Best Girl (1927) neither of

which Rosher had seen in years.

Heart o' the Hills impressed Kevin in terms of its

technique but also Pickford’s range; “characters no sooner look at each

other, than they exchange blows…” The hillbilly dance is “a classic sequence”

featuring the ethnic authenticity director Sidney Franklin was looking for.

Kevin also singled out art director Max Parker for his creation of the

backwoods locations and living spaces; as he says, there was nothing “cutsie” or

sentimental about this endeavour and the producer herself also has to take

great credit for that… Kevin concluded by saying:

|

| Pickford's character shows her scars from maternal beatings... |

I suspect Kevin was preaching to the already converted

but this is indeed a wonderfully spirited film and one that treats its audience

with respect, another key element of Pickford’s approach. After all, she was a working-class

women just like most of her audience, her agenda was to deliver the kind of stories

they understood and morality they would agree with in a tough environment they

would recognise. We don’t talk enough about silent film stars and class, except

to note that they “escaped”, but I don’t think Mary, or Charlie and many

others, pulled the ladder up.

Here Mary is Mavis, who’s father was shot in the back

when she was young and whose mother Martha (Claire McDowell) has been worn down

over time, fighting to keep going in their ram shackled homestead. Her best pal

is young Jason Honeycutt (Harold Goodwin) who takes her out on fishing trips –

some worms were sadly harmed in the making of this film – and other larks.

Jason’s father Steve (Sam De Grasse) is the opposite of

fun and, as we quickly learn, many other things including honesty, fairness and

virtue. He’s hard on his boy and Mavis while targeting Martha, her hand and,

her land which, as Mavis shows Jason, is rich in coal, surprising for such an

elevated location but there you go.

|

| Hootenanny show-down! John Gilbert on the left. |

Money comes to town in the form of “forrigns” Colonel

Pendleton (W.H. Bainbridge) and his entourage including son Gray (a surprise

appearance by young John Gilbert, just 22 here and on the brink of stardom) and

his intended Marjorie Lee (Betty Bouton). Also with them is the scheming Morton

Sanders (Henry Hebert) who is plotting with Steve Honeycutt to grab Martha’s

land and swindle as much of the community as possible.

There’s a great confrontation between the two at the local hop, where Gray, who has caught the eye of Mavis and vice-versa, joins the dance only for Jason to try and out-manoeuvre him in a kind of strictly-come-country dance-off. In the end Mavis joins in and a proper scrap is narrowly averted.

Soon though she has worse to come as Steve pushes Martha to marry him and orders her to leave home. She takes her issue to the locals, led by her wise Granpap Jason Hawn (Fred Huntley) and they decide that dressing up in white hoods and costumes to confront the land-grabbers is the way to resolve this.

|

| Don't mess with Mary... |

Now I’m not sure why it is that certain Americans like wearing their

sheets in this way but I’m also not convinced it’s a Ku Klux Klan moment –

although it might well be. It ends badly though as someone shoots Sanders and,

of course, given motive, opportunity and her outspokenness, Mavis is soon

standing trial accused of his murder.

As Kevin Brownlow points out, this film doesn’t pull its

punches and the stakes are high. Mavis’ character also stays true to herself and

the resolution is worth the wait. It’s an entertaining film with that mix of

humour and grit our great grand parents knew and loved to see on screen.

Pickford is mighty as you’d expect and Rosher packs as many glorious head shots

in as possible as we watch her unconscious naturalism lead the emotional

charge!

We were watching a 35mm print made from an original copy

at the Mary Pickford Foundation and it was full of rich textures and stunning

depth of field. This is one of the real pleasures of the Bioscope, the

connection between the audience, the celluloid and the general ambience of this

unique venue. The atmospherics are also heavily informed by the subtlety of the

accompanist and in this case it was Colin Sell who not only as Kevin predicted,

showed his powers of controlled syncopation for the dancing sequence but also

played along so sympathetically with Pickford and the rest of the players.

|

| The British version of the sheet music |

We were also treated to a wonderful performance of the

song released to accompany the film from Colin and the Bioscope’s MC Michelle

Facey. On BBC programmes you sometimes witness “experimental” archaeologists

attempting to recreate certain processes to illustrate and find out more about

the techniques and the “taste” of the period. The Bioscope is a working example

of this experimentalism and Facey and Sell recreated another key element of the

spirit of this film and the emotional reaction this song would have brought.

Glenn Mitchell had a copy of both the US and UK version of the sheet music and

naturally we went with the British copy. Loveliness ensued… and the film was

set up!

Early Mary…

White Roses (1910) directed by Frank Powell was

screened first on a 16mm from Chris Bird’s collection and, whilst its plot was

a little outlandish, it was all good fun with Mary’s character Betty for some

reason in love with a very shy man called Harry (Edward Dillon). Harry hasn’t

the courage to ask her directly so her arranges to send three colours of

flowers to her and a note saying that she should wear red for yes and white for

no… Sounds simple but he gives the task to a young lad (Jack Pickfor, who’s

other sister, Lottie is also involved), who promptly gets robbed of note and

flowers.

A well meaning man steps into help and buys replacements

but there’s no note and so Betty wears white forcing Harry to propose to his

cook in retaliation… That’s not the end of things but you really have to watch

this to believe it! John Sweeney accompanied and suspended all our disbelief in

the process.

|

| Mary and Elmer wait for the law... |

The Narrow Road (1912) directed by D. W. Griffith

on rare and possibly singular* 16mm print made from a nitrate original by

legendary collector John Cunningham, now from Chris Bird’s collection, the film

is only otherwise preserved in the Library of Congress paper-print collection

as a paper copy of the celluloid made for copyright purposes. It was another of

the unique Bioscope occasions, watching Mary married to ex-convict played by

the great Elmer Booth, who is torn between going straight at a wood merchants and

his loyalty to fellow con and recidivist forger, Charles Hill Mailes.

Ashley Valentine accompanied with lovely lines and in

tune with this short but powerful tale. As Michelle said in her introduction,

some say DW was at his best for these Biograph shorts and on the evidence of

this and others, I’d have to agree but part of that is down to the contribution

of players like Pickford who would eventually fall out with him and others,

such as Booth who would die tragically early in a car, driven by an inebriated Tod

Browning.

+colour.png)

No comments:

Post a Comment