As online presentations go, Hippfest at Home is perhaps the most successful in capturing the atmosphere and the feeling of actually being there. You have establishing shots of the live introductions shot from the back of the stalls showing the lovely old stage of the oldest cinema in Scotland, the Hippodrome (1912) and then the option of seeing the film and the musicians accompanying. As always, Alison Strauss leads from the front with such relaxed expertise and enthusiasm – this kind of impassioned poise is reflected across the whole team who love the films but also the audience and the combination is what makes this impossible festival work so well it is now in it’s 15th edition.

The hottest ticket for this year was as Alison said, Mr Neil

Brand who gave the most entertaining talk about his singular career from his

first professional accompaniment – Buster’s Sherlock Jnr (1924) – to his most

recent – in the most “meta” moment he had to improvise to a mystery film

selected by Alison. Neil, always so eloquent and, damn it, charming, had

my entire family rapt as Dad’s choice suddenly engaged them all – “ah Georges

Méliès!” said the son lured away from his PS5 – “I really must see Nosferatu…”

said the daughter and “so that’s my friend Netti’s old landlady!” said my wife watching

Cecil Hepworth’s eldest Elizabeth aged two who we met in Camden in the 1990s in

her 80s. Even Mungo the dog was of course transfixed by Rover, the Hepworth’s

dog, who outwits a kidnapper by driving his getaway vehicle back home…

something to aspire to young pup but not in my car!

Neil had updated a show and tell he’d previously performed

at the Edinburgh Fringe and it was a story not just of his career and method

but also silent film and its revival over the last few decades. He talked of

his audition with the BFI and how his acting training had helped inform his

response to Sherlock Jnr, a quite intimidating work from an actual genius who gave

signals not just to his audience but also the players he knew would accompany

his film. Neil recalls the exact moment when the audience’s reaction inspired

him to follow Buster’s promptings in ways he hadn’t anticipated.

|

| Neil Brand |

Dullard that I am, I’ve mostly focused on the silent film

live experience from the perspective of accompaniment and film without really

understanding the impact the audience reaction to both has on the player and

vice versa. Every action has an equal and opposite reaction and this is a Mobius

Strip of emotion and anticipation. Neil showed Robert Siodmak, Edgar G. Ulmer and

Billy Wilder’s People on Sunday (1930) and got the audience to score the

mood by a show of hands during key moments. Not only were our anticipations

split on the direction of Wilder’s smart scripting, but Neil was able to

flavour the narrative in ways that reinforced the second-guessing. It was a virtuosic

performance all round from a consummate communicator.

We had the wonders of Méliès’ hand-coloured Impossible Voyage

(1906), the dark-heart of the definitive vampire film, Murnau’s Nosferatu

(1922) and finished off with a clever home movie called Early Birds which was a

colour film from the fifties (? nowt on IMDN but it was Alison’s Mystery Film

after all!) in which a baby escapes from his cot, totters along the hall,

shuffles down the stairs and makes a mess in the kitchen. It was delightful and

Neil talked us through his musical reaction to this most unpredictable of

delights.

It was genuine family entertainment and all on Catherine’s

birthday too – the best thing on telly!

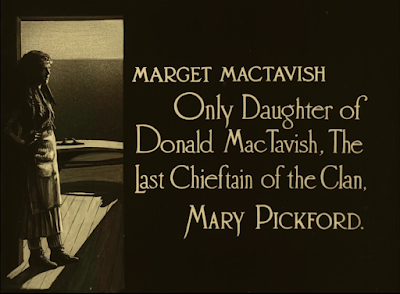

The Pride of the Clan (1917), with Stephen Horne

and Elizabeth Jane Baldry

There was also drama on a grander scale from one of the

great originators of the art of film performance, Mary Pickford in Maurice

Tourneur’s The Pride of the Clan (1917). This was a recording of the

Friday night gala introduced by Alison and the doyen of silent filmography,

Pamela Hutchinson both of whom looked like they’d just stepped off the Oscar’s

red carpet. This film was also accompanied by the dreamy team of Stephen Horne

and Elizabeth Jane Baldry who had previously accompanied the fabulous The Swallow

and the Titmouse (1924) a film that really suits their combination of piano

and harp.

Mary plays Marget MacTavish who takes over as Chieftain of

the clan after her father drowns at sea. She’s about to marry Jamie Campbell

(Matt Moore) and there’s some silliness with couples in the clan biting

sixpence in half so they can hang it around each other’s necks – HG Wells

should have sued! But it’s all in fun even when Jamie is revealed to be of

noble blood and his birth mother tries to sweep him away to polite society. Yeah,

good luck with that lady, this is Mary P you’re contending with…

Tourneur’s locations are well chosen to create a genuinely

Caledonian feel and the FOMO was real as Elizabeth-Jane’s harp Oberon

added further Celtic magic along with Stephen’ expert innovations as the silent

film equation gained an extra element with the two telepathically in tune with audience

and each other following Mary’s lead on screen. I saw this film in Pordenone but

it was presented here in the way that only Hippfest can: the fifth

element!

The Near Shore: A Scottish and Irish Cine-Concert,

with Patrick Smyth

As someone who is more Irish and Scottish than English – what

do you expect from Liverpool la’? – I was especially impressed with the

selection of the five films that made up this Cine-Concert. These shorts were

all from the IFI Irish Film Archive and National Library of Scotland Moving

Image Archive and introduced by Sunniva O’Flynn from the IFI – you cannot understate

how international Hippfest is, with collaborators from Norway and Sweden, over

to the Americas and beyond.

It began with the earliest known film made by an Irishman, Royal

Clyde Yacht Club (1899), which featured a race in the Firth of Clyde and

then Ireland by Air – featuring Scottish aviatrix Winnie Drinkwater

(1933) which also returned via the Firth with stunning views of my favourite Isle

of Arran and a mist-covered Goatfell. Before that we saw shots of Galway –

historical family location of The Joyces – and an Ireland still between the

centuries with ducks and donkeys in the streets mixed with grand municipal

buildings.

As a former Butlins employee – a Hi-de-hi-d for two summer

seasons in my youth – I was impressed with Butlins camp photographer John

Tomkins’ tow films – Butlins Holiday Camp and Rush Hour (1950s). Tomkins

filmed the inmates, sorry holiday-makers, and then screened the films so they

could see themselves at the end of the week. This is so much in the spirit of

Butlin’s and I especially loved the one in which the children take over, robbing

the redcoats blazers as they are frozen by some child’s magic… it was all,

literally a dream.

|

| Galway, 1933. |

Finally, there was The Farm below the Mountain (1958),

Scottish filmmaker Ernest Tiernan’s record of his travels with his young bride

Kathleen to meet her family in rural Ireland… so familiar and in beautiful home-movie

colour. We have something like this at home… maybe not so well shot!

The films were accompanied by renowned Irish avant-garde

pianist, Paul G. Smyth who overlayed some lush textures on these films just out

of memory and so full of human commonality. In the Hippodrome there’s no separation

by time, we’re all connected as elements of the live cinematic mix, even from

home we’re at the Hippfest home.

Until next year then and a visit in person, I think the

family are convinced now! Thank you all for the wonder and the show.

+colour.png)

stays on topic and states valid points. Thank you.

ReplyDeleteThe account helped me a appropriate deal.

ReplyDelete

ReplyDeleteYour style is really unique in comparison to other people

Exactly where are your contact details though?|

ReplyDeletePretty portion of content.

ReplyDeleteDamn! I'm in love! It's beautiful!

ReplyDeleteIt's simple, yet effective. D.

ReplyDeleteI must say you have done a awesome job with this. D.

ReplyDeleteIn addition, the blog loads extremely fast for me on Internet explorer. D.

ReplyDeleteKeep up the superb works guys I've included you guys to my blogroll.

ReplyDeleteAmazing! This blog looks exactly like my old one!

ReplyDeleteSaved as a favorite, I really like your web site!

ReplyDelete