Out of the blue and into the black

They give you this, but you pay for that

And once you're gone you can never come back

When you're out of the blue and into the black

Dennis Hopper took the title for this film from his friend

Neil Young’s song My My, Hey Hey (Out of the Blue) which ruminated on

the fleeting nature of “relevance” and fame in the wake of The King’s death and

the emergence of Johnny Rotten and seemingly nihilistic punk rock. It’s also a call to be,

like Young, true to yourself at whatever the cost… and, clearly, we can see why

he and Mr Hopper got on so well.

Hopper hadn’t directed a film since The Last Movie (1971)

and was only supposed to be an actor in what was intended as a family-friendly

drama until it was clear that the original concept and team were not going to

work out. Hopper had been very impressed with the presence and style of his

young co-star, Linda Manz (then a rather diminutive 19 years old) and had

an idea to turn things around with her at the centre.

Hopper took over directing a week into production,

rewriting the script with producer, Leonard Yakir and Brenda Nielson before starting

principal photography from scratch. What emerged is about as far from the

original concept you could imagine and a story which encompasses some of the

most unsettling moments in a stunningly off hand way… a narrative that drifts like

life before smashing the watcher full in the face. Now newly restored in 4K,

with a lorry load of highly impressive extras, his film comes to Blu-ray for

the first time in the UK thanks to the BFI who clearly know what they have

here.

|

| Linda Manz and Dennis Hopper |

We get some quotes from Hopper which help explain why he didn’t

make more films, he claimed to be the world’s worst listener and that he wouldn’t

collaborate with anyone else, all save his actors (imagine being a fly on the

wall for his direction of Jack Nicholson in Easy Rider?!). Manz is the perfect

match for his style in a film he only gained control of when the production company’s

back was against the wall, and the two deliver an astonishing film.

The film starts with a moment of sheer terror that feels

like something torn from a Paul Auster novel, the impossibly horrific crash of

a juggernaut into a stalled school bus. The driver is Don Barnes (Hopper) who

is drinking and distracted by his young daughter Cindy aka Cebe and doesn’t see

the danger until it is all too late. It is only later that Hopper shows us the

moments of the crash but we’re left to imagine the full extent as Cindy/Cebe

wakes up years later and we hope it’s just a nightmare until the camera moves

out and across the wreck of her father’s old cab, windscreen smashed were his

head hit it and where she gained two noticeable scars.

Imagine the guilt and the consequence? Well, Dennis hasn’t

finished with us yet. Not by a long way…

It’s five years later and whilst Cebe has grown up in a most

peculiar way, tomboyish, she fixates on Elvis Presley and punk, parroting Sex

Pistols lines and Punk aesthetic such as “kill all hippies”, as she chats to

truckers on the CB radio in her dad’s old cab who have even less idea what she

means than they do.

|

| Linda Manz |

Cebe’s lost and attracted to the nihilism of Punk and the manly style of The King, she’s lonely too, on the outside at school and willing to be outrageous to impress the few friends she has. Her mother Kathy (Sharon Farrell) works in a diner and is having a relationship with the straight and tolerant manager Paul (Eric Allen) who is unaware of her heroin habit and fondness for fooling around with Charlie (Don Gordon) one of Don’s old pals.

Talking of which, Charlie’s on hand to lead the leering as Cebe

and her fellow 15-year-olds go bowling… it’s so casually done and all the more

shocking for it especially as he then goes and paws Kathy right in front of

Paul. Later Cebe sees her mother shooting up heroin with Charlie at their house

which prompts her to escape to Vancouver for a night of adventures which again

almost sees her sexually assaulted by a Cabby (Carl Nelson) and his prostitute

girlfriend in a mixed-sex brothel.

Cebe does have one glorious moment as she goes to see Vancouver

punk band Pointed Sticks who welcome her backstage and even get her to join

them on drums for one song. It’s her one moment of pure joy as she’s amongst

non-judgemental people who love music and ask nothing of her… they may look

like plastic punks to those of us of a certain age in the UK but they’re welcoming!

|

| A cold welcome |

She returns home and sees a child psychiatrist, Doctor Brean played by Raymond Burr who was to have been a larger part of the original story and here feels like a brief punctuating break of normality.

This family is a hard one to save especially as Don returns

from prison to a mixed welcome from the community with the fathers of the

children he killed in the crash out for revenge. He tries to reintegrate with

society by driving a bulldozer on a waste site and to pick up where he left off

with his wife and daughter. There’s the rub and more shocks are in store as the

broken family is not so easily fixed.

Manz is indeed extraordinary and she’s a one-off with an out

of kilter freshness cut from the same cloth as Hopper himself… her career was

relatively short but she left her mark with this film and Terrence Malick's Days

of Heaven for which she beat out one Jodie Foster!

|

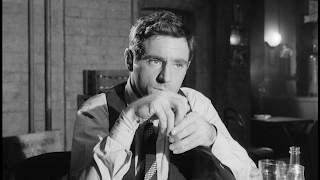

| He never phones it in... always in the moment. |

The BFI have gone longer than usual on the extra special features

on this release which will delight Hopper fans:

·

Audio commentary with Dennis Hopper, producer

Paul Lewis and distributor John Alan Simon (2000)

·

New commentaries by Kate Rennebohm and Kat

Ellinger

·

Dennis Hopper interviewed by Tony Watts (1984,

97 mins)

·

Screen Guardian Talk: Dennis Hopper (1990, 91

mins, audio only): the filmmaker talks to Derek Malcolm

·

Subverting Normality: Linda Manz Comes from

Out of the Blue (2021, 18 mins): a new video essay by Amanda Reyes and

Chris O’Neill

·

Remembering Out of the Blue (2021, 174

mins): nine new interviews with cast & crew

·

Me & Dennis (2021, 95 mins): four new

interviews with Hopper’s friends and colleagues featuring Ethan Hawke, Richard

Linklater, Julian Schnabel and Philippe Mora

·

Alex Cox Recalls Out of the Blue (2021, 13 mins)

·

Montclair Film Festival Q&A (2020, 30 mins):

John Alan Simon and Elizabeth Karr discuss the history and restoration of the

film

·

Jack Nicholson radio spot (1982, 1 min)

·

Trailers

There’s also a selection of complementary archive shorts

– Morecambe and Wise – Be Wise Don’t Drink and Drive (1963, 1 min), Drink

Drive Office Party Cartoon (1964, 1 min), A Girl’s Own Story (Jane

Campion, 1983, 27 mins); Girl (Carol Morley, 1993, 7 mins)

There’s also a gorgeous Illustrated booklet for the first

pressing only with essays by Sheila O’Malley and Vic Pratt; an extract from

Dennis Hopper: how far to the Last Movie?, originally published in the Monthly

Film Bulletin, October 1982; two reviews from 1981 and notes on the special

features.

Out of the Blue is out now so make all haste to

click on this link to the BFI shop and buy it! It’s a stunner!!

+colour.png)