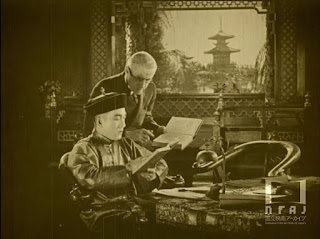

Unlike his ancestors, Tsu Ya Woug Shih follows the principles

of Western culture. He loves according to his heart…

The New York Times thought this film a standard movie

melodrama and that “Mr. Hayakawa is worthy of something more genuine…” and yet,

in Japan, future Toho producer, Iwao Mori, praised it for its authentic

depiction of “Eastern ways of thinking.” Mori even went so far as to call

Hayakawa “an unofficial diplomat…” to be supported by a Japanese public who were

initially less impressed with his roles as the bad guy in films like DeMille’s The

Cheat (1915).

By this point Sessue Hayakawa was in a more powerful position

in Hollywood and this was the twentieth film made by his own production company,

Haworth Pictures through which he was able to play more of the hero. This

progression was much welcomed in Japan according to his biographer Daisuke

Miyao from San Diego University who was on hand for the post-screening

discussion. He estimates that only some 40% of Hayakawa’s silent films survive

which makes this restoration from a 35mm nitrate print at the Jugoslovenska

kinoteka, Beograd, all the more important.

|

| Learning Western ways |

Where Lights Are Low is evidence of the

actor/producer’s appeal and he has star power to burn with ridiculous good

looks, focused expressiveness as well as action hero athleticism – his big brawl

with the film’s equally impressive baddie, played by Togo Yamamoto, is

clothes-ripping, choke-holding, nose-bloodying authentic in the manner of

Hobert Bosworth; exhausting to watch.

Whilst I can see the Times’ point of view – this is a

melodrama and it does have moments of cultural cringe - it shows how off the

pace they were in terms of recognising both the uniqueness of the star and the

effectiveness of the film’s production. Colin Campbell’s direction is smoothly

assured and there’s a wonderful set-piece in a ballroom that cuts between the

elegance of the dancing and the reactions of Tsu Ya Woug’s uncle on his

first trip to the West. He looks down in amazement at the dancers’ graceful

cohesion and imagines the jazz band as Chinese; cultures crossed in one

cross-shot.

|

| Sessue and Gloria Payton |

That said, as Professor Mori states in his notes, Hayakawa’s

company was being run by the Anglo-American Robertson-Cole company who were

setting the agenda in terms of productions that conformed to fans’ “Orientalist

imagination of Asia”. But their star was still intent on authenticity – even though

he is playing a Chinese character – and this shows in the commitment to

portraying both the eastern and western environments.

The set design is superb and the overall aesthetic from

China to San Francisco’s China Town is high quality even if the latter was

based on photographs less than experience; this is a well-resourced

undertaking!

The story is from Lloyd Osbourne, a stepson of Robert Louis

Stevenson, and tells of a Chinese nobleman who is intent on following Western

ways not least in matters of the heart. He is in love with his gardener’s

daughter, Quan Yin, played by Gloria Payton who, in unconvincing make up and

with limited range is the film’s biggest weakness. It’s strange casting to

modern eyes when you consider that the rest of the oriental cast is either of

Japanese or Chinese origin but despite acting with his wife Tsuru Aoki in The

Dragon Painter and others, Hayakawa seems mostly to have been restricted to

either Caucasian actresses or love interests.

|

| Introducing Uncle to new pals |

His Uncle is having none of it and has plans for Tsu Ya Woug

to marry the socially acceptable Jae; “nobles are not allowed to choose

according to their own will… “

Tsu Ya Woug heads off to America to train as a lawyer

although I’m not sure what relevance this will have to his noble

responsibilities back home, and vows to return for Quan Yin. Four years on he’s

qualified so well he’s dressed in a smart evening suit playing craps with his

buddies in a backroom when his uncle comes to find him.

Meanwhile, in Chinatown, the police are looking to crack

down on human trafficking and fail to look deep enough into a consignment of

tea chests that includes a drugged Quan Yin hidden beneath the Oolong. She’s

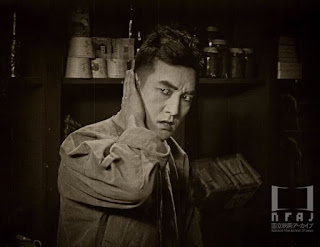

taken for auction where local mobster, Chang Bong Lo (Togo Yamamoto) is

determined he’ll buy her for himself. Yamamoto is just fantastic here, he looks

the part and acts with real menace and unpredictability, especially in one

later scene when he confronts our hero by throwing a rotten banana at him. He went

on to make many Japanese films including Yasujirō Ozu’s Sono yo no tsuma

and Ojosan.

|

| Togo Yamamoto |

Anyway… back at the auction Tsu Ya Woug, slumming it,

walks in to find his love for sale and bids $10,000 to buy her back. Unfortunately,

his Uncle refuses to fund his investment of the heart and he ends up having to

work for three years to raise the money himself. Confusingly he doesn’t do this

by using his legal training but by washing dishes and then opening a grocery

store where he encounters his rival for the aforementioned fruity face off.

Even when he eventually raises the money though he will

still face opposition from Chang Bong Lo when it turns out that, surprisingly,

money can’t buy you love and you have to fight for it!

Accompanist extraordinaire, Philip Carli, is very familiar

with Campbell’s work and described him as a “penny plain, tuppence coloured

director… very straightforward” yet, this film he found to be much more

colourful than the director’s usual fare, presumably because of Hayakawa’s drive

for realism. Philip said that the fight sequence is reminiscent of the fight

Campbell filmed in The Spoilers (1914), but silent film scraps could be

brutal.

|

| Grocery grievance |

In musical terms Carli had to approach the film carefully

because he didn’t want to fall into the obvious “traps” of an American film on

an oriental subject. He aimed to keep the musical inflections as light as

possible, and, as with everything in silent accompaniment, he knows exactly how

to step back in the overall mix allowing the flavours of the images to speak

for themselves. His playing delivered showing, what he described as “sensitivities

towards the culture of the film making as well as the characters on screen…”

He lifted the film and complimented the heroic Hayakawa so

well that I almost felt I was in the Teatro Verdi… looking forward to the after-show

Aperol Spritz.

Next year!!

+colour.png)

No comments:

Post a Comment