‘There is nothing connected with staging of a motion

picture that a woman cannot do as easily as a man and there is no reason why

she cannot completely master every technicality of the art.’ Alice Guy

Blaché

Like London buses, you wait years for a box set of early

women film pioneers and then four of them arrive almost all at once. This BFI

set is the latest and for those wondering which to buy I’m here to make the

case for this over Flicker Alley, Lobster and even Kino Lorber, although in the

latter case you really should buy both with the caveat that the Blu-ray version, which has the most content, is Region A and you'll need a compatible player.

|

| Making an American Citizen (1912), unique to the BFI set |

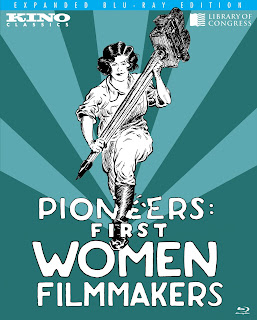

The Kino set is six Blu-ray discs and, of course, has a

greater range of material than the others but it dovetails pretty well with the

BFI set and together they give you 8-9 discs of unique, must have, material

from an era that is only now being fully rediscovered. Even in the span of my relatively

recent interest in early film, the directors in this set have been re-evaluated

with pioneers like Guy Blaché and hugely popular filmmakers like Lois Webber

been restored to their rightful position. There are some great films on these

sets and they help to broaden our appreciation of the new media as one not just

dominated by Méliès, Griffith, de Mille et al.

Kino goes long on Alice Guy Blaché with 14 films from 1911

to 1913 of which the BFI replicates five and adds two, Making an American Citizen (1912) and The Girl in the Armchair (1912). Only Flicker Alley covers her

earlier work with Les Chiens Savants (1902), Une Histoire roulante

(1906) and La Barricade (1907).

|

| Guy Blaché's utterly lovely Falling Leaves (1912) |

Guy Blaché pretty much invented narrative film making as

Pamela Hutchinson explains in her essay in the excellent BFI booklet which also

allows the contributors to comment on each film. There are two films not

covered on Kino, Making an American Citizen (1912) and The

Girl in the Armchair (1912) with the former taking the director’s

experience of immigration and turning it into a proto-feminist fable. As PH

notes, equality in marriage is a condition of acceptance in the new country,

and the heroine, played by Blanche Cornwall, sees her husband Ivan abandon his

domineering Euro-bullying to fit in with the New World after various American men step in to force him to adjust his behaviour.

It’s not just the fact of these films but their themes;

there is a different sensibility at work and a willingness to tackle subjects

from within rather from on high (and yes, DW, I’m looking at you).

|

| Claire Windsor and Louis Calhern in The Blot (1921) |

Nowhere is this more in evidence than in the films of Lois

Webber whose work often contains a depth and intimacy that others lack. The BFI

set includes The Blot (1921) which is not only one of her best but also

one of the most impressive character-based dramas from the period, its tale of

bourgeois poverty trap, neighbourly jealousy and conflicted love delivered by

superb performances especially from Webber discovery Claire Windsor as the

librarian at the centre of a love triangle between an educated but poor theology

student and a wealthy Phil West played by Louis Calhern (who I’ve just seen in

the BFI’s smashing restoration of Notorious (1946)). Her mother is also

well played by Margaret McWade who hangs on in quiet desperation as the family

suffers daily humiliation from their immigrant neighbours who make a healthy

living through trade. There’s no right or wrong to either side and Webber’s

take is sophisticated to stand the test of time better than Griffith’s

Victorian morality tales.

|

| Triangulated tension - Lois top right in Suspense (1913) |

Webber tackles social issues with an even-handedness that

eludes many and Discontent (1916) about an old man who is happier in his

old soldiers’ home than with his well-intentioned relations, is another

example. Her technical skill and innovation are also evidenced by a crisp

restoration of the superb Suspense (1913) famous for its three-way split

screen and overhead point-of-view shots: it’s a genuinely pioneering and tense

story of home invasion on a par with anything coming out of Biograph.

Kino has 13 Lois Webber films including noteworthy features

such as Too Wise Wives (1921), Hypocrites (1915) and Where Are

My Children? (1916) yet, apart from the spectacular Suspense (1913),

the BFI disc alone includes Discontent (1916) and The Blot (1921).

I’m beginning to suspect collusion…

|

| Here's Mabel! |

The BFI set gives you by far the most Mabel for your money

with five films of which Mabel's Dramatic Career (1913, 14 mins), His

Trysting Place (1914, 22 mins) and the magnificent late period riot Should

Men Walk Home? (1928, 28 mins) are unique to the BFI set. Mabel’s a marvel

and I especially enjoy the rawness and energy of her work with Chaplin in Trysting

and Mabel’s Strange Predicament (1914). Mabel directed the former

and, probably, co-directed the second which sees Charlie progress from

irresponsible parent to slightly chastened – and battered – husband; these two

were making up so much content on the hoof and had improvisation to burn.

Mabel’s adventures are also marvellously accompanied by the

Meg Morley Trio who’s tight, jazz-age playing catches the mood and movement of

Mabel’s quicksilver narratives.

|

| That's not how we rehearsed it Charlie... |

None of the material on the third and fourth BFI discs is available on the Kino set and one of the main delights is a film from Olga Preobrazhenskaya,

regarded as the first female Soviet filmmaker. Kat Ellinger’s essay reveals

that little is known about the director and that whilst many of her films are

lost, what survives reveals a concern for character over propaganda even though

the film included here, The Peasant Women of Ryazan (1927) could be seen

as an attack on the Kulaks (rich peasants) who were viewed as in the way of

industrialisation/modernisation by

Stalin’s regime.

The Kulak in question is Vasilii Shironin (Kuzma

Yastrebitsky) who allows his son, Ivan (G Bobynin) to marry Anna (R Pruzhnaya)

a poor girl from the neighbouring village, only to rape her when he is away in

the First World War. Anna has her father-in-law’s baby but has to live in

disgrace with the village not knowing the cause of her shame. Shironin’s

daughter, Vasilisa, (Emma Tsesarskaya) is the face of the new Russian woman,

forging her own destiny by deciding who she marries and setting up an

orphanage.

|

| Damned by tradition and a Kulak's greed (R Pruzhnaya) |

Even as the villain of the piece, Shironin has shame and

regret and there’s a lot going on in a narrative that is true to itself and not

just instructions from on high. There are some superb sequences of rural life

showing the vibrancy of a culture that was under threat even just over a decade

after the story was set. The performances are also excellent especially from R

Pruzhnaya as the long-suffering Anna and from Emma Tsesarskaya as the modern

Vasilisa. Ellinger has this as a feminist film but sadly things were to get

worse in the ensuing decade and beyond.

|

| The face of the future? Emma Tsesarskaya's character makes her own decisions. |

Marie-Louise Iribe has already made a stylish impression on

me in Hara-Kiri (1928) which she co-directed with Henri Debain’s and in Le

Roi des aulnes (1929), her only film as sole director, she proves to have

an uncanny style all her own. Based on Goethe’s poem Erlkönig (1782) and

Shubert’s song of 1815, it features a father battling through a forest to take

his sick son to a doctor. The two confront all manner of imagined horrors in

the deep woods as the Erl King magics up fairies to obstruct their purpose, as

if the illness wasn’t real enough…

Last but not least is The Woman Condemned (1934), an

early talkie from Dorothy Davenport also known as Mrs Wallace Reid, wife of the

film actor who died from drug addiction in 1923, who was determined that his

death would not be in vain and that she would fulfil her own ambitions. Ellen

Cheshire’s essay details Davenport Reid’s determined creative drive after being

widowed as she wrote, produced and directed films with a social conscience. She

transitioned to sound films and The Woman Condemned, an entertaining but

over-worked and under-budgeted crime film that features an outstanding

cross-examination scene with Claudia Dell giving her all.

|

| Under pressure: Claudia Dell |

Cheshire quotes Ivan Spear in Boxoffice (13th May 1939) wondering

why so few women ‘attain high production or executive niches in the [film]

industry and, further, why those few women who have done so have failed to stay

at the top’. Davenport Reid was one of those who he said had “dropped from

sight” but she continued working as a scriptwriter into the fifties and deserves

to be remembered as a filmmaker in her own right and not just a widow.

The set also includes a snippet from Dorothy Arzner’s Dance

Girl Dance (1940) along with Mary

Ellen Bute’s experimental Parabola (1937). There are also three short

featurettes on Mabel Normand, Alice Guy-Blaché and Lois Weber: fascinating

lives and there’s a lot more to come in their rehabilitation as all the essays

make clear.

|

| Smoking is bad for the health... |

I’ll leave the last word to Germaine Dulac writing in ‘Ayons

la Foi’ Le Film (1919):

‘The time has come, I believe, to listen in silence to

our own song, to try to express our own personal vision, to define our own

sensibility, to make our own way. Let us learn to look, let us learn to see,

let us learn to feel.’

The BFI set is full of these “songs” and it’s essential for

all who want to listen. Available now from the BFI Shop on and offline.

The Kino-Lorber set is also available direct from their site and a reminder that it is Region A so you'll need multi-region capability. It features a mind-boggling range of filmakers including Nell Shipman, Alla Nazimova (Salome in great quality!), Ida May, Julia Crawford Ivers, Frances Marion - her feature Song of Love (1923), starring Norma Talmadge - serial queens, Grace Cunard and Helen Holmes and more (two silent features from Dorothy Davenport Reid!). There's a 40% discount at the moment and together with the BFI set, this wonderful box set opens up a whole new-old world of cinematic and social history.

+colour.png)