This was an extraordinary evening in the presence of a

remarkable man who probably needed an all-nighter to get through all of his

amazing stories from a life encompassing boxing, drumming, poetry, directing,

acting, writing, painting and then back to film. His last film, EO (2022)

was Oscar nominated and is out on BFI Blu-ray on 3rd April, his next

film is due later this year written for some guy he met through a mutual

appreciation of jazz – then illegal – back in Iron Curtain Poland in 1956,

Roman Polanski.

Born in 1936 or probably 1938, Skolimowski explained that

his mother had had to change his birthdate so that he would qualify for support

post-war. During the war he was trained to play act as a happy child, jumping

up and down on his bed when the Gestapo made a call, hiding the fact that there

was a printing press underneath it, used by his parents to spread the news of

what was actually happening. His father was executed by the Germans and after

the war, in recognition of his parents’ activism, he was sent to a special

school in Prague were his dorm included future filmmakers Miloš Forman and Ivan

Passer, whilst future Czech President Václav Havel, was also there.

Jerzy wanted to make his mark and this began with

attempts at being a poet – he joked (perhaps) of visiting libraries to steal

his books so that no one could read how bad they were – jazz drumming, he

couldn’t really keep time, and amateur boxing which taught him to keep his eyes

open during every blow so that he knew how to recover and take evasive action.

Lessons in life. When his chance came with film, he grasped it with the same

alertness and co-ordinated aggression, writing scripts and then planning out a

full feature film based on his four student projects in film school.

|

| Michael Brook, Jerzy Skolimowski and his partner/co-writer Ewa Piaskowska |

His films in Poland – and Belgium – during the sixties

established his name and then he went too far into politics for the authorities

to bear, a four-eyed Stalin in Hands Up!, being enough to ensure they

delivered his passport as the biggest hint to leave. He came to the UK, where

he knew no one, and made the sublime Deep End (1970) with Jane Asher and John

Moulder Brown. The dialogue was partly improvised and it was the smartly

experienced Asher who came up with the “de-facing Government property” line

when she rips up a poster promoting contraception.

By now time was running short and we didn’t get much further than Moonlighting (1982) the making of which is as fascinating as the film itself and says much about the director's generosity and determination. Essentially in 1981 when Poland was put under martial law, Jerzy came across a crowd of Poles outside a hotel where he lived who were now without a country to return to, he took them in and found a place for every one through friends and looking up Poles in the phone book; just head to the sectionwith names starting "Sz..." Then, he decides to make a film about his country's hour of need, persuades Channel 4 to back it, Jeremy Irons to star in it and theatre impressario Michael White to also fund it through a mid-tennis match sales pitch. Another extraordinary circumstance and the resultant film is one of those I'm most looking forward to seeing on the big screen.

Props to film writer Michael Brook for digging into this rich history and we literally could have gone on well into the next day had scheduling not intervened for Jerzy's uncanny masterpiece, The Shout (1978), was due to screen and he had to prepare himself for his introduction. Before he spoke though there was a unique introduction from Mark Jenkin who had taken the extraordinary step of a Cornishman, to cross the border into Devon, to seek out the locations of The Shout in ways that only he can. Is the soul of the story to be found in the spaces between the locations, Saunton Sands, the church of St Peter in Westleigh and Braunton Burrows, or in the stone and the land itself, echoing the themes of the film itself?

|

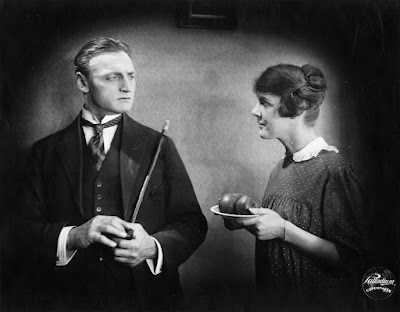

| Alan Bates |

The director described this film as his happiest experience

in filmmaking and that it was mostly down to his producer Jeremy Thomas, well

that and the 200 Thai Sticks they were going to quote as a dedication at the

end of the film! The film is indeed one wild trip but that’s more down to the

story and setting as well as the performances from a remarkable cast to which

he credits Thomas’ powers of persuasion. For himself, Jeremy is equally

impressed with his director: “Skolimowski had a sense of shooting style

then, this was the second director who I had worked closely with, and it was

fascinating watching Skolimowski work. He came from a Polish tradition, the

Wajda Film School, he had a different background to other directors… And it

made the film much more creative to me. I saw it more as an artistic endeavour

by him.”

The film features electronica from Rupert Hine who

started out as a fold musician but ended up Chair of the Ivor Novello Awards having

had hits of his own as well as producing everyone from Tina Turner to Rush and

Underworld. The composers of the main theme and incidental music were Tony

Banks and Mike Rutherford of the progressive rock combo, Genesis*, then extremely

out of fashion but about to conquer the world with the aid of drummer Phil

Collins.

Rutherford and Banks went to Charterhouse as did,

coincidentally, Robert Graves whose story provides the basis of the film, a mysterious

tale of a man who claims to have supernatural powers that is told largely in flashback

during a cricket match played at a mental hospital. Jerzy was very keen to film

a cricket match but this is unlike any you’ll have seen – of course – and I’m

still having nightmares about a nearly naked Jim Broadbent running around in

only his cricketer’s box and covering himself with cow dung. Jim worked with

Ken Campbell early doors, what can one say?

The film’s flashback begins after Susannah York rushes to

a remote hospital after an incident, crying “where is he?” before entering the

billiard room in which three dead bodies are laid out under clothe. We don’t quite

catch the faces before the scene changes to the pastoral calm of a cricket

match as a young Robert Graves (Tim Curry) arrives in his whites. He meets the

head Doctor (Robert Stephens) who introduces him to a man known as Crossley

(Alan Bates), whom he describes as the most intelligent man in the place.

Crossley and Graves are set to score the match and as

they watch it unfold from the edge of the pitch, the former begins to tell his

strange tale involving his involvement with a couple who, he considers, have

lost their way in their marriage. Anthony Fielding (John Hurt) is an experimental

composer working away in his home studio supported by his wife Rachel (Susannah

York). Whilst we have already seen Susannah, John Hurt is one of those out on

the cricket pitch… we assume now that they’re the same characters and, they

might well be.

In Crossley’s story, we see him engineer a meeting with

Anthony after he has been playing the local church organ and had a secret

assignation with a young married woman (Carol Drinkwater), he starts talking to

Anthony about his faith and ends up following him home and inviting himself to

lunch and to stay. Gradually he reveals his strangeness and his past decades

spent in the Australian outback during which, in addiction to apparently

killing any offspring as his right under their supposed rules, he learned much

magic including the ability to kill men with his voice, The Shout or The Scream.

|

| John Hurt, Alan Bates and Susannah York, a talented table |

He pushes both of the couple’s sensibilities and the

viewer is left wondering what is real and what is simple fantasy but there are

so many layers as events unfold.

The cast is, of course fabulous, but its Bates who

dominates with his thousand-yard stare and a restless power that continually

wrongfoots expectation and social norms unsettling both those o and off screen.

It’s a very centred performance that conceals as much as it reveals and only

generates more mystery as the story is fully revealed.

The film was nominated for the Palme d'Or at the 1978

Cannes Film Festival and received the Grand Prize of the Jury, in a tie with

Bye Bye Monkey.

The Jerzy Skolimowski Season continues into April andthere are full details on the BFI site.

The BFI are also releasing the Oscar nominated EO

(2022) as well as a double set, Identification Marks (1964) the film he

made over four years at film school and Hands Up! (1967) the film that

got him exiled from Poland, on 24th April.

_-_Ad.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

%20combined%20age%2036.JPG)

%20suitor.JPG)

%20theatre%20look%201.jpg)

.jpg)

%202.jpg)

.jpg)

%20bath%20towel%207.jpg)

.jpg)

%20blue%20steel%202.png)

.png)

%20reviewing%20the%20options.png)

%20blue.png)

.png)

%202.png)

%20baby.png)

%20baby%202.png)

%20mirror.png)

.png)

.png)

+colour.png)