If I were an architect and had to build a monument to

cinema, I would place a statue of Duvivier above the entrance. This great

technician, this rigorist, was a poet. Jean Renoir, Mémoires

Given the widely quoted proportion of missing silent film

it’s amazing how much is still extant which can surprise, uplift and thoroughly

engage. This mood-altering beauty, La divine croisière en français, was

all but lost at sea and was splendidly restored in 2020 by Lobster Films from a

variety of sources; an abbreviated nitrate print used for Pathé Baby 9.5 mm home

cinema, four different 35mm fragments and two 17.5mm diacetate Pathé Rural

prints including shots that were censored. The results are on the absolutely

essential Cinema of Discovery: Julien Duvivier in the 1920s set

from Lobster/Flicker Alley – nine films including Au Bonheur des Dames

(1930) – which was released earlier this year: the uncovering of a veritable “cinematic

Atlantis” as described by Serge Bromberg, Lobster’s leader.

Due to wedding commitments, not mine but the next

generation are in a post-pandemic rush, I can’t make the screening but I would

urge everyone who can to do so, book now, stop reading and go straight to the BFI website, you will not be disappointed with film or accompaniment; this is

going to be a revelatory show.

|

| Suzanne Christy and Jean Murat |

There is so much pleasing late-silent technique on show

from Duvivier in this film – Renoir’s “rigorist poet” in action – with a roving

camera that moves in and out of buildings, follows crows as they race to the

harbour side or to confront wrong-doing. Close ups of locals cast for face and

rapid cutting that shows the influence of both Russian and German directors,

not to mention intense close-ups that rival Dreyer for impact. The locations,

Paimpol in Brittany, Louvigny sur Mer in Normandy and Ermenonville, now in a

national park northwest of Paris, are superbly photographed and edited to

create an impression of a people on the edge, battling unforgiving nature.

Against this backdrop Duvivier, who wrote and directed,

presents a story of faith, bravery and class conflict. The film’s critique of

blind capitalism is one of the reasons it was heavily censored at the time, and

it begins with an act of desperate revolt when a mariner Kerjean (Henri Valbel)

who has defaulted on his rent, attempts to assassinate unforgiving businessman Claude

Ferjac (Henry Krauss), Ferjac in his chateau. Ferjac runs the town with a callous

calculation and he will push the citizens to the brink before the story is

through.

|

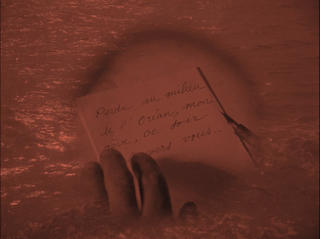

| Almost the opening shot... |

On the run Kerjean encounters Ferjac’s daughter, Simone (Suzanne

Christy) who, for a few moments he considers killing her but she is a completely

different proposition to her father who connects with the locals and shows

compassion. We cut to the Kerjean’s house being emptied and see that his wife

has killed herself… but none of this cuts any ice with Ferjac, who threatens a

child who throws a stone at his limousine… property is more important than

people’s lives.

Times is also money and Ferjac makes it clear to the

local mariners that manning the insufficiently repaired La Cordillère is

of far more importance than the risk to their lives. Captain Jacques de

Saint-Ermont (Jean Murat) makes their case but he knows there’s no way of

changing Ferjac’s mind. The meeting between the boss and the sailors shows the

hatred and fear they feel for this man and the desperate calculations they have

to make for their families.

There’s further intrigue with Simone romantically

attached to Jacques and the two meet in the bay, separated by a fishing net,

both trapped in their relationships with her father who will listen to no one be

it the curate (Louis Kerly) or Jacques mother (Charlotte Barbier-Krauss, who also

featured in Carrot Top (1926) also on the Lobster set and Duvivier’s

favourite film.)

|

| Simone and Jacques, caught in the net |

The ship sets sail and includes the last-minute arrival

of a mariner from outside the area, Mareuil played by Thomy Bourdelle who gives

a stand-out muscular performance as the faithless opportunist upon whose

actions so many lives will rest. Simone visits the Curate in his church and

dedicates herself to repainting the frescoes and especially the painting of

Maris Stella, she who is the “Star of the Sea”.

Things swiftly go awry on the voyage as Mareuil decides

that stealing the cargo is the way forward – another heartless capitalist? –

and persuades most of the men to revolt, throwing one unfortunate who refuses

into the sea to drown. His group overpowers the Captain and his men, taking

control just before the sea, as it was always going to do, erupts in a storm that

would challenge even the finest of ships.

Back on land, the body of the murdered man is found and

there’s a harrowing passage as his wife, Jeanne (Line Noro in her first feature

film of what would become a long career) is told of the news and leads a march

to confront the man responsible. Ferjac is busy hosting a lavish dinner party

to announce the marrying off of Simone to one of his business contacts, she cannot

even hold her glass to toast the depressing nuptials and then Jeanne arrives

followed by dozens of the locals who are now convinced that the ship has sunk

and there’s only one man to be blamed.

|

| Roughhouse Thomy Bourdelle |

NO SPOILERS!

This is only the narrative entrée though and the Divine

Voyage is yet to really begin… there’s a magical realism at play and faith,

fate and hate will all have their role to play as the full story enfolds.

Duvivier maintains not only the pace but also a startling

consistency of cinematic expression throughout as well as bringing out some

extraordinary performances. Watchable on so many levels, The Divine Voyage is

indeed as Serge Bromberg suggests, as glorious a discovery as you would expect

from an unearthed cinematic Atlantis.

Do not miss it on screen if you can make it. You can book here.

The Duvivier box set is available from Flicker Alley and

Lobster Films.

+colour.png)

No comments:

Post a Comment