And so we came, by planes and boats and trains, back to

the home of silent film festivals, Pordenone North of Venice and a very fine

town indeed. My first time here since 2019 having been stymied by the lockdown

and then by C-19 itself but not this year in spite of attempts by wild

publishing horses to keep my mired in gobbledegook: get thee behind me Croydon!

Before the biggest of finishes we were served a reminder of

the importance of this festival, breadth, rarities, new discoveries and men on

horseback. Star of the Day was Pauline Frederick in The Love That Lives (1917)

which had some foreshadowing of The Crowd and Stella Dallas… Pauline made me

cry in 2019 with Smouldering Fires and she had me welling up again with her

performance in this dramatic tragedy. She had a pair of the most penetrating

eyes in Hollywood and here she looked so much younger as a put upon young

mother who is preyed on by her boss and her drunken husband.

Her transformation by the end would have made even L Gish

baulk at the physicality, she looked thirty years older yet still with enough

love and grit to provide divine inspiration. Philip Carli accompanied with sensitivity

and spirit.

|

| Pauline Frederick |

Meanwhile, in Ruritania – Part 2 of the GCM’s deep dive

into mythical monarchies – there was some confusion in La reina joven

(1916), a Spanish film – rare to see one of this vintage for me – as a romance

between a Queen and an anti-monarchist went in ways that you might not expect. Said

Anti-Royalist Rolando (Ricardo Puga) bravely rescues the young Queen Alexia (Margarita

Xirgu) after her horse bolts and he throws himself around the beast’s neck to

bring it to a halt… we almost saw it, but the editing was not so brave as the hero.

Anyway, once Alexia fails to die from the shock – the levels

of distress-induced female mortality were so high at this time, someone should

have investigated – things progress in resolutely non-romcom ways, as despite

their romance, neither will change course. Oh, if only there was an evil Archduke

to stir things up and thereby avoid criticism of legitimate political concerns

about the Spanish system of government… Ace accompaniment was from Mauro

Colombis who had fun with all the regal romance and that horsing about.

|

| Queen Alexia takes to horse |

A horse, a horse, my kingdom or a horse, yelled one

British King according to Shakespeare, but Harry Carey had loads of horses, exactly

when he needed them. Carey’s a handsome cowboy and it’s a treat to see the festival

highlight him in his pomp after only really seeing him in talkies and with his

good friend John Wayne (The Searchers, that final shot… Wayne standing

at the door with his hand holding his arm like Harry used to, magnificent).

Carey’s a fabulous actor and has lots of physical motifs

that indicate concern or casual thoughtfulness, a thumbnail stare here, a pensive

thumb to the lips there… he might well have been studying Asta Nielsen. All of

this plus his ability to fight and act make him a magnetic screen presence and

these three simply whipped by with Stephen Horne riding along with gusto.

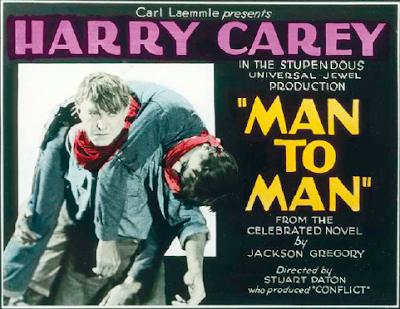

Most striking of all was the partially two-strip tinted Man

to Man (1922) directed by Stuart Paton which featured some outstanding

vistas and dynamic action as Steve Packard (Harry C), fights to clear his name,

rescue the family ranch and win the heart of Terry Temple (Lillian Rich). To do

this he must overcome the extreme disapproval of his grandfather, Old Hell-Fire

Packard (Alfred Allen) and his confederate, Joe Blenham (Charles Le Moyne) who

is the wrongest of wrong-uns.

Again, it’s striking how much of the wild western formula

was in place this early with an impressive mass stampede of cattle organised by

the baddies to ruin the ranch and the extended man-to-man combat of the closing

sequence. Then there’s Harry who was rightly lionised by Wayne, he’s the real

deal and I look forward to watching more of his gun-totin’ horseplay as the

week unfolds.

The Divine Voyage (1929) with Antonio Coppola and the

Octuror de France, Gala

I missed this one last year at the BFI and so was

especially keen to see it on the big Verdi screen and with a stunning new score

from Antonio Coppola who conducted a nine-piece ensemble who translated his dynamic

lines and simply gorgeous themes to accompany this magically-real story of hope

and faith in spite of everything from capitalist carelessness to mutinous

muscle men and the cruel sea itself. The music was packed with interest and

recurring themes that are still replaying in my head and all done in the

service of Julien Duvivier’s striking narrative and sumptuous visuals. The

whole village turns out to wave ships off in good hope and to cheer their return,

well the global Pordenone village does the same for works and music like this!

Brava Antonio and the Octuror de France ensemble.

There is so much pleasing late-silent technique on show

from Duvivier in this film – Renoir’s “rigorist poet” in action – with a roving

camera that moves in and out of buildings, follows crews as they race to the

harbour side or to confront wrong-doing. Close ups of locals cast for “face” that

rival Dreyer for impact and rapid cutting that shows the influence of both

Russian and German directors. The locations, Paimpol in Brittany, Louvigny sur

Mer in Normandy and Ermenonville are superbly photographed and edited to create

an impression of a people on the edge, battling unforgiving nature. Were you

watching Michael Powell?

The film’s critique of blind capitalism is one of the

reasons it was heavily censored at the time, and it begins with an act of

desperate revolt when a mariner Kerjean (Henri Valbel) who has defaulted on his

rent, attempts to assassinate unforgiving businessman Claude Ferjac (Henry

Krauss), Ferjac in his chateau. Ferjac runs the town with a callous calculation

and he will push the citizens to the brink before the story is through. Times

is very much money and Ferjac makes it clear to the local mariners that manning

the insufficiently repaired La Cordillère is of far more importance than the

risk to their lives. Captain Jacques de Saint-Ermont (Jean Murat) makes their

case but he knows there’s no way of changing Ferjac’s mind. The meeting between

the boss and the sailors shows the hatred and fear they feel for this man and

the desperate calculations they have to make for their families.

There’s further intrigue with Ferjac’s daughter Simone

romantically attached to Captain Jacques and the two meet in the bay, separated

by a fishing net, both trapped in their relationships with her father who will

listen to no one be it the curate (Louis Kerly) or Jacque’s mother (Charlotte

Barbier-Krauss).

The ship sets sail and includes the last-minute arrival

of a mariner from outside the area, Mareuil played by Thomy Bourdelle who gives

a stand-out muscular performance as the faithless opportunist upon whose

actions so many lives will rest. Simone visits the Curate in his church and

dedicates herself to repainting the frescoes and especially the painting of

Maris Stella, she who is the “Star of the Sea”. Things swiftly go awry on the

voyage as Mareuil decides that stealing the cargo is the way forward – another

heartless capitalist? – and persuades most of the men to revolt, throwing one

unfortunate who refuses into the sea to drown. His group overpowers the captain

and his men, taking control just before the sea, as it was always going to do,

erupts in a storm that would challenge even the finest of ships.

Back on land, the body of the murdered man is found and there’s a harrowing passage as his wife, Jeanne (Line Noro) is told of the news and leads a march to confront the man responsible. Ferjac is busy hosting a lavish dinner party to announce the marrying off of Simone to one of his business contacts, she cannot even hold her glass to toast the depressing nuptials and then Jeanne arrives followed by dozens of the locals who are now convinced that the ship has sunk and there’s only one man to be blamed. It’s a powerful set piece – fake elegance rudely interrupted by anguished poverty.

This is only the narrative entrée though and the Divine

Voyage is yet to really begin… there’s a magical realism at play and faith,

fate and hate will all have their roles as the full story enfolds. Duvivier

maintains not only the pace but also a startling consistency of cinematic

expression throughout as well as bringing out some extraordinary performances.

What a way to end this first day back “home”, as festival

director Jay Weissberg said in quoting his predecessor, David Robinson.

No comments:

Post a Comment