Well, here's another clue for you all, the Walrus was

Paul… John Winston Lennon, Glass Onion

Let me take you down to the Piazza Maggiore, nothing is

real and there’s nothing to get hung up about… There’s no limit to the Beatle

references I can fit into this stuff so, anyone of you in the cheap seats can clap

whilst those in the sponsored area just rattle your jewellery because this is

my personal selection of mini-reviews for screenings that struck me in the eight

days a week that was Il Cinema Ritrovato 36th Edition… Eight halves

as it were and most certainly not definitive. There's more...

As you would expect, my week was mostly silent but the

joy of this festival is firstly that there are half a dozen choices at any one

point and secondly you can go eclectic at any point you choose, when it’s just

too hot to walk all the way to Silent Town at the Sala Mastrioannie, or you just

really need to see what Peter Lorre is doing or what Sophia Loren is wearing.

It’s All Too Much, as I believe George Harrison once sang, but that’s the

beauty, after a mad few days of completism – gotta see them all! -

exhaustion, hangovers, sore feet and failing concentration demands variety!

1. Ménilmontant

(1926) with Stephen Horne

There were quite a few films I’d already seen but this

new restoration was something else with Lobster films restoration not only

adding clarity to the images – Nadia Sibirskaïa’s freckles have never been

clearer – but also tinting which adds so much to one of the most beautiful of

silent film. There was also the revelation that director Dimitri Kirsanoff was

not actually a Russian emigre but from Estonia whilst Nadia was from Brittany;

the two having adopted the more exotic background as part of the vogie for

creative emigrees from Russia?

Whatever their reasons, the films they produced were esoteric

and distinct even shot in the middle of Paris and this ethereality was enhanced

by the new colours and, of course, Stephen Horne’s way with sympathetic and emphatic

accompaniment. It was the most perfect blend of “special” audience, film and

music. Not for the last time this week, the restoration of a film I thought I

knew really brought new depth of meaning and fresh response.

The same could be said for Timothy Brock's splendid new orchestral score for Nosferatu (1922) which, watching him conduct the Orcestra del Teatro Cimunale di Bologna in the Piazza Maggiore, was as good a screening as I've seen, revealing much new about this very familiar film and helping the audience access a narrative of broader meaning. Good job sir!

2. Superheroes…

Protéa (1913) with Maud

Nelissen

There were some interesting early serials, pre-dating the

works of Louis Feuillade and with a focus on the works of Victorin-Hippolyte

Jasset with his evildoer Zigomar and endless adversary Nick Carter seemingly

engaged in a non-stop exchange of capture and escape. Far more engaging was woman

of mystery Protéa played by Josette Andriot, who was not only a mistress of disguise,

she also had a male sidekick called The Eel (Lucien Bataille) so called because

of his ability to squeeze in and out of tights spots.

Protéa was far more stylish in all ways, with disguises

and a plot that was thoroughly entertaining and not, even by 1913 standards,

hackneyed. She wears a black body stocking two years before Musidora as Irma

Vep and needs it too to practice her martial arts and physical daring. Not surprisingly

her protean quality and striking looks insured that four other episodes

followed. Well, I’m onboard for more screenings and for the box set if at all

possible.

Maud Nelissen accompanied with sisterly dynamism,

supporting our heroine as she leapt from conclusion to capture and freedom,

outwitting her captors time after time.

|

| Jean Valjean (Henry Krauss) and his nemesis Javert (Henri Étiévant) |

3. Les

Misèrables (1912) with John Sweeney, Gabriel Thibaudeau and Silvia Mandolini

Talking of serials, this was an unexpected joy equalling

in its own way, the lengthier silent serial of 1926. Based in four parts totalling

168 minutes in length it was split into two screenings and, like a true serial

left you wanting more – see above).

The first parts, focusing on Jean Valjean and then

Fantine, dealt economically well with the complexities of the source material

and was genuinely gripping as our hero made his way from humble beginnings and

his arrest for stealing bread for his dying mother, to imprisonment then escape

where his huge strength of character and physique enable him to take control of

his own destiny always pursued by his nemesis, the unforgiving Walmer.

John Sweeney’s accompaniment gave the classic support

this film required and the audience were on the edge of our seats before

leaping off for the cheering applause. We were back the next day for Gabriel Thibaudeau’s piano

and Silvia Mandolini’s violin to provide equally pleasing musical support as the

focus shifted onto Fantine’s daughter Cosette, whom Valjean, having promised to

support, rescues from a miserable family who use her as little more than a

slave. Valjean once again makes a fortune and sets Cosette up for love with

Marius a radical student who takes part in the battle of the barricades to try

replace the post-revolutionary republic with an more egalitarian one. Recommended

for fans of French history and film alike. An extraordinary clarity of purpose

from Albert Capellani, way ahead of many at this time.

%202.jpg) |

| Glamour in Tu M’Appartiens |

4. The

Diva endures… Tu M’Appartiens (1929), with Daniele Furlati

I don’t recall seeing anything with Francesca Bertini, one

of the three great Italian Divas of the 1910s after that decade and yet here

she is in this French film towards the very end of the silent era and her

screen career, looking as proudly beautiful and emotionally nuanced as ever:

the eternal diva.

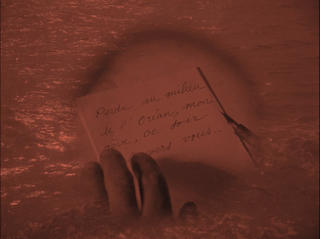

Directed by Maurice Gleize, Bertini plays Gisèle a woman

who is intent on gaining revenge for long ago being dumped by Rudolf

Klein-Rogge’s Burat Laussade a reformed criminal who long ago escaped justice

and the penal colony to build a new life for himself married to the

nice-but-not-Bertini, Suzy Vernon. Under French law, anyone who manages to stay

free for 20 years after the offence is able to avoid prosecution and, Laussade

is quietly approaching that safety line before Gisèle catches up with him with

her operatically grand revenge: she, naturally, wants it all.

The pace of the second half is especially intense and we

get the chance to see Bertini ease through the gears like an emotional explosive

device that sucks the air from your lungs as you hold your breath just watching

her shift from violent resolve to heard-breaking compassion with audacious

precision. They never made another one like Francesca and this is a precious

film.

We watched a new sparkling 4k restoration from Gaumont in

collaboration with CNC – Centre national du cinéma et de l’image animée presso

il, and when it comes to the UK and elsewhere, is not to be missed. Daniele Furlati accompanied, enhancing the drama and working at the same esoteric levels

as Bertini and, to be fair, Klein-Rogge who knew a thing or two about guilt,

all the better to portray some innocence here.

5. Roscoe

returns… Crazy to Marry (1922) with Donald Sosin

Having recently seen a presentation on the ill-fated and entirely

innocent Mr Arbuckle, how he was kept working by his mates like Buster and how

he almost made it back only to die young with a heart attack. Had it not been

for the false accusation of rape this is the kind of film he would have made

more of; just imagine, a body of work that may have been as inventive and as

funny as Buster’s, Harry’s and Charlie’s?

Directed by James Cruze, this was a laugh riot from start to

finish with Roscoe on top form with every facial trick, forlorn look to camera

and that extraordinary trademark prat fall when he shifts his bodyweight to

fall flat on back or front. Donald Sosin accompanied his old friend, thousands

of hours shared between them on sight and sounds.

|

| Jean-Louis Trintignant |

6. The

Conformist (1970)

Screened on the opening day in the Piazza Maggiore; a

film about how fascism works in front of a largely Italian crowd, who applauded

it long and loud at the end. I can’t think of many similar films for the UK,

maybe parts of Gandhi, but can you imagine Oh, What a Lovely War being

screened in Trafalgar Square and the Daily Mail and various commentators saying

it was traitorous. Strange times for us Brits and this film is even more

essential viewing given the recent drift towards intolerance in public

discourse.

The late Jean-Louis Trintignant is of course, incredible as

Marcello Clerici, faithless civil servant happy to help out the secret service

in the matter of “dealing with” his former friend and teacher, the

wrong-thinking anti-fascist Professor Quadri (Enzo Tarascio). Marcello travels

with his fiancée Giula (the ageless Stefania Sandrelli who was on hand to

provide the introduction) who seems to reflect more his desire for normalcy than

romantic connection. He’s also accompanied by his handler, Special Agent

Manganiello (Gastone Moschin) and things get very complicated when Marcello is

attracted to Quadri’s lover, Anna (Dominique Sanda) who is also attracted to

Giula.

Marcello sees marriage as the way to fit in and, whilst

he certainly has some fear of his own true sexuality, this is not the only

thing forcing him to make compromises that cost him friends, lovers and anyone

but himself. He’s a survivor, he’ll do and say anything. Terrifying.

A 4k restoration from an original camera negative by the Cineteca

di Bologna, in collaboration with others, it was magnificent on the Maggiore’s

huge screen, a feast for the eyes and with ever more complex puzzles for the

conscience.

|

| Down on the street was my friend Charlie, taking a break from Bunjies folk cafe... |

7. Get

Back (2021), with John, Paul, George and Ringo

Peter Jackson’s extraordinary three-part reworking of The

Beatles Let it Be sessions, recorded at Teddington and Apple Studios in January

1969, has already been streamed but watching it with the thousands in the open

air of the Piazza Maggiore, was something else indeed. You may not like this 60-year-old

pop group but for some generations it’s musical magic, beyond nostalgia. If you’re

from Liverpool and your Dad went to school with John and lived near George,

then there’s not only local pride but community involved.

Jackson’s film allows us the most intimate access to

their working methods and also completely blows away the bad taste of the

original Let it Be film which focused on the negative. Here there’s the natural

dialogue between very close friends and the piss-taking of a strong group. At

one point Paul and John discuss the recording’s direction and it’s a startling

moment as the two look directly into each other’s eyes, with even Ringo and George

on the periphery; this is core band discussion, no producers, directors or

wives… We see the creation of some epic tracks, even Octopuses’

Garden, alongside Paul’s epics hymns, Let it Be, Long and Winding Road and the

rocker Get Back.

Everything culminates in the Apple Building Roof Top

concert and this has never been fuller of more extensively covered. You feel The

Moment and the vox pop support from all ages in the streets below runs

alongside a triptych showing differing camera angles. Then the Police arrive

and Macca turns round to whoop with extra energy, Mal Evans unplugs an amp, but

George plugs it right back in and Lennon, already transformed by performing

live, rises up a notch, Time travel doesn’t get much more visceral.

Film, plus audience and memories… we got back alright.

|

| Maria Jacobini, the hills are alive. |

8 Cainà: La Figlia

Dell'isola (1922), with Laura Agnusdei, Tullia Benedicta, Stefano Pilia and

Cecilia Stacchiotti

Under the sky at the splendid carbon arc projector fired

up at the Piazetta Pier Paolo Pasolini this film

was confused by my late arrival as well as an electronic

score that was sincere but just too emotionally inflexible to add much to the

rather lovely images and dynamic central performance. Having now rewatched the

whole film my impressions are reinforced with Gennaro Righelli’s film making

the most of the Sardinian locations on land and sea as well as the remarkable display

from Maria Jacobini as Cainà a part she co-wrote.

Cainà lives with her goats and conservative parents in a

small farming community on the island and is on course to marry local boy Giannatola

(Sig. Carmil) but she dreams of escape and the world beyond, even just the

mainland. A boat arrives and she listens intently to the stories from the

sailors. She stows aboard their ship and leaves, being discovered by the captain

Pietro (Carlo Benetti) as a fierce storm strikes almost sinking the ship but

killing her father on land. Unaware of the tragedy back home Cainà follows

Pietro, much to his two sister’s disgust, and struggles with his expectations

as well as life in a town.

It's a classic tale of restless youth and Cainà will find

that she has no home wherever she goes… as the critic P. Amerio, wrote in the December

1923 Rivista Cinematografica, Maria Jacobini … expressed with

admirable effect… the eternal fatal torment of the restless wanderer.

8 ½… C'era una volta (1922)

Sophia Loren in a dish washing competition with seven princesses, Omar Sherif being a mean old Prince riding horses and a squadron of flying saints... what more needs to be said?!

There’s more, of course there’s more… and there’s

a number of films I shall be writing about in more detail over the coming days

but it’s been fun!

Grazie mille Bologna, everyone who took part, who

screened and who played, who organised and who served! See you in 2023!!

%20tom.png)

%20look.png)

%20farm.png)

.png)

%20dance%202.png)

.jpg)

%202.jpg)

+colour.png)