`Why do you want to dance?' `Why do you want to live?'

A film about ballet for people who don’t necessarily like ballet, a populist “art” film and a fairy tale where the magic is provided by human drive and imagination… The Red Shoes isn’t straightforward at all but then what Powell and Pressburger film ever is?

The centre piece of the film is the 17 minute Red Shoes ballet which abandons any pretence at theatrical reality by taking off into a cinematic flight of fantasy that Gene Kelly could only dream of. The film is magically real – perhaps the very peak of The Archers’ trademark style and one that confused their distributors so much that they never gave it a proper premier in the UK. Unable to reconcile the adult content in what they presumed was a family film, Eagle Lion all but buried The Red Shoes until a record-breaking response in New York lifted it to international success and eventual recognition as one of the greatest films ever made.

From this distance you can still understand their response and this film isn’t as far away from Peeping Tom as you might think, as Moira Shearer’s presence in the latter may well prove. Miss Shearer was a prima ballerina with the Royal Ballet, perhaps second only to Margot Fontayne in London at the time. So, unlike Black Swan for example, here we have a actress who can actually - really - dance and who moves with the dangerous grace founded on the bruised flesh and cracked ankles of a thousands days’ practice. She is authentic and fascinating: a delicate beauty, whose sensitive features are crowned by a mass of rust-red curls and set atop a body perfectly poised: you can really only be this way if you have no other choice.

|

| Moira Shearer, |

My wife, a redhead herself and no mean ballet dancer in her youth, was suitably impressed – solidarity of colour and tone. The reds… they know more than they let on.

.jpg) |

| Robert Helpmann, Moira Shearer and Léonide Massine |

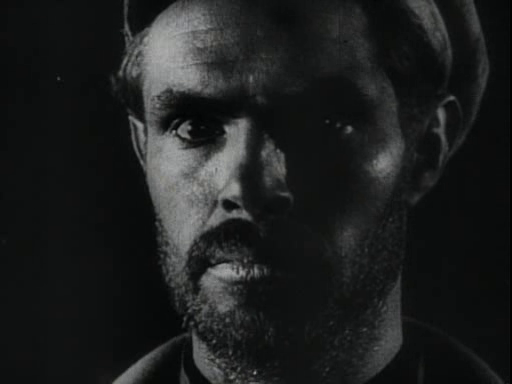

But the non-dancing cast was also well-chosen and none more so than Anton Walbrook who’s Boris Lermontov manages to be maniacally controlling and also strangely vulnerable. He carries a natural authority and with trademark restraint manages to underplay a role that could so easily fall flat through an excess of grim single-mindedness. Boris just needs to find beauty in his art and even the prospect of being danced to in the inappropriate surroundings of an after-show party is too much for him to bear.

|

| Anton Walbrook and Léonide Massine |

Vicky’s inevitable rise is held back by Powell as she joins the ranks of hopefuls in Lermontov’s troop and we’re immersed in the life of the ballet. Also involved is a young composer Julian Craster (Marius Goring) who has impressed the great director with a composition that has been ruthlessly stolen by his music teacher. Lermontov points out that it is better to be capable of producing such a work than to have to steal another’s creation and commissions him to write a new ballet, The Red Shoes…

|

| Marius Goring |

Simple enough questions on the face of it but Powell and Pressburger succeed in walking the line between clarity and complexity and, in Moira Shearer, they have an acting presence capable of expressing actual hard-won genius on screen. Everyone else is posturing (albeit skilfully) but she demonstrates the end product… she’s the real deal.

The music by Brian Easdale is another element that has to be as good as the story demands: his music is the soul of Craster and an expression of his love for Vicky. Brian takes this near impossible brief in his stride though and his compositions are wonderful, especially for the Red Shoes ballet itself – the only section he didn’t conduct, that was left to the mighty Sir Thomas Beecham. Easdale went on to win the Oscar for Best Original Music Score: the first Britain to do so.

Some films get lodged in the “canon” by reputation alone but The Red Shoes is one in which every major component is no less than excellent… it’s a film about ballet sure enough but also the most basic questions of life: this is why it continues to resonate and to retain its power.

If you don’t already have it and you probably do… the Criterion Collection version is superb and the UK Blu-Ray uses the same transfer (I think?). Movie Mail has the latter plus DVDs whilst you’ll need Amazon.com for the former. You can also buy Brian Easdale's soundtrack on CD.

“Why do you want to watch classic film…?' because they're entertaining. Not quite as good is it...?

+dancer.jpg)

+steps.jpg)

+snow.png)

.png)

+2.png)

.png)

.png)

+memories.png)

.png)

+lost+2.png)

.png)

.png)

+turmoil.png)

.png)

+Laughing-Gassed+German+Soldier.png)

+watching.png)

+1.png)

+2.png)

.png)

+library+snap.png)

+HE+1.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

+daisy+chain.png)

.png)

.png)

+sad.png)

+HE+angry.png)

+colour.png)