Though they would work together again, this was the last

film Powell and Pressburger made through their Archers production company and

as with the first of their collaborations it was a war story shot in black and white.

Much had changed in the intervening 18 years and, unusually for the pair, this

was not an original story but one based on the memoires of W Stanley Moss who

was indeed involved in the successful kidnap of the German general Heinrich

Kreipe, commander of the German forces on Crete. Kreipe was successfully shipped

off to Egypt and only released in 1947. He was reunited with his kidnappers on

a Greek television programme in 1972… and, an educated man, much like the British

officer who led the audacious mission, Major Patrick "Paddy" Leigh

Fermor the two apparently remained friends. Kreipe perhaps was a real-life

example of one of the Archers’ “good Germans” exchanging Latin quotes with Paddy

during his capture.

For today’s screening there was much delight when we arrived

to find that the last two members of the cast, Dimitri Andreas (80) who played

the young Niko and George Eugeniou (now 92) who played Charis, introduced the

film in an interview with Jo Botting, Curator of the BFI’s National Archive.

Both men were still passionate about their director’s work, it was Dimitri’s

first film and he had been introduced to Powell by George as he was looking for

a boy who had experience with goats. He has gone on to have a long career in film,

incredible how the World can turn with one chance encounter, but seeing his

youthful energy you can understand what Powell saw in him and why his talent has

endured.

|

| George Eugeniou, Jo Botting and Dimitri Andreas |

George Eugeniou also shares this disposition and talked not

only of Powell but also his involvements with Joan Littlewood as a member of

her theatre company and then his role in Sparrows Can’t Sing (1961) one of the

classics of kitchen sink drama and her only film. He featured in small parts in

both Pressburger’s Miracle in Soho as well as Powell’s Peeping Tom and is still

angry at the way that film effectively ended the director’s mainstream career

in this country, especially when compared with Hitchcock’s more clearly

exploitative Psycho. George founded the Theatro Technis Company Limited in 1957

and has dedicated most of his career there with the aim of presenting

"radical and total" theatre aimed at breaking down barriers between

nationalities, religions, genders, sexual orientations, classes, ages and

languages. The Technis is still a vibrant presence based in Crowndale Road in

Camden and more details can be found on their site.

It was a privilege to see both men and to learn of the

impact the film and the Archers had on them and, as Dimitri then came and sat

beside me in Row D, to watch them on screen, 67 years ago, on the BFI’s 35mm

copy was the kind of surreal treat you only get on the Southbank; the audience

and the filmmakers watching film as history, history as film…

|

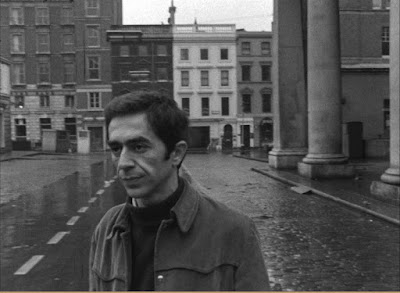

| Dirk Bogarde and George Eugeniou |

George plays one of the local Cretan resistance fighters, mountain

“wolves” waiting to prey on the fat German sheep who populated the valleys

during the occupation. Major Patrick "Paddy" Leigh Fermor (Dirk

Bogarde), also known to the locals as Philedem, after a traditional Cretan song

he liked so much his comrades used it as his nickname. He’s undercover

travelling to one of his Cretan contacts to discuss his audacious plan of abduction

with a local (Wolfe Morris) who suggests that commandeering the general’s car

is the only chance even though this will mean passing through numerous roadblocks.

Another British officer, Captain W. Stanley "Billy" Moss (David Oxley) arrives on the island and we get to meet the rest of the team, Captain Sandy Rendel (Cyril Cusack), who hasn’t washed for six months, Zoidakis (a barely recognisable Michael Gough with huge moustache), car-spotter Elias (John Cairney), Yanni (Paul Stassino) and the excitable Charis (George Eugeniou). Plans are made and the team lies in wait, stopping the car with Paddy and Billy dressed in German police uniforms before knocking out the driver and driving off with the General (Marius Goring) squashed under three men in the back seat.

|

| Dimitri Andreas |

They successfully evade capture, speeding through the road

checks – 22 in all – and escaping to the hills before the Germans realise that

their commander is missing. Now the adventure really starts as the small unit

has to escort the General at altitude across the hills to rendezvous with a British

boat. On their way they encounter a young boy, Nico (Dimitri Andreas) who helps

them pull the general along on a donkey – Geneva Convention dictating that

capture generals deserve appropriate travel provision – runs local errands and

ends up playing a crucial role.

Along the way, there’s ample opportunity for Goring and Bogarde

to trade glamour and tonality, whilst the cinematography of Chris Challis is of

course splendid although what we’re seeing is not Crete but the Alps Maritime in

southern France near the Powell’s hotel; how the crew musts have loved humping

their heavy cameras up to those “views”.

At the crucial point neither of the British officers knew

the morse code to contact the Royal Navy motor launch ML842 and they had to wait

for another officer – in this case Sandy – to turn up and show them how. I have

seen this listed as an example of the film’s shortcomings but it’s absolutely

the case. The gods were with the Cretans and British that night.

|

| Dirk and the actual Paddy... |

Powell vs Pressburger…

As with their previous film, The Battle of the River

Plate (1956), the fourth most popular film in Britain in 1957, Ill Met

also did good box office being the seventh – the films were released just six

months apart - and yet the cracks were certainly appearing between the two

creators and, more to the point, around them. Powell described it as one of The

Archers' "greatest failures” in Million Dollar Movie (Heinemann, 1992)

and partly blamed Emeric’s script although he was also disappointed in Dirk

Bogarde, a great actor but “a charmer… as subtle as a serpent, and with a will

of steel.” Dirk gave the film a lighter tone and didn’t follow direction,

drawing the other actors with him, all except regulars Goring and Cusack one

imagines.

For his part, Kevin Macdonald quotes his grandfather in The

Life and Death of a Screenwriter (Faber, 1994), about the contract dilemma they

faced with John Davis, a situation which would restrict their independence but

would guarantee more productions. He’d become a good friend of Leigh-Fermor and

whether this made him over-think the script is anyone’s guess but he and Powell

just could not agree on the film’s narrative objectives. Macdonald mentions

that the location was a constant issue, chosen partly because of the difficulties

in Crete at that time but also to assuage Powell’s then girlfriend. Dirk

Bogarde is quoted on the intensity of the ill-feeling which impacted the entire

set and film editor Judith Buckland was amazed that the bitter disagreement she

saw did not ruin the men’s friendship.

At the end of the day, what we saw on screen still has

moments of magic, Goring know the score and gives good General (he had made it

to Colonel in the war) whilst Bogarde couldn’t help but give a Byronic twist to

the Englishman on an daring mission – he had also served in the army from 1943,

mainly as an intelligence officer. David Oxley is less convincing as Captain

Bill Stanley Moss but his role is less well developed, yet he’s likeable enough

as are the rest of the troop* in what stands as a celebration of a remarkable action.

And, returning to the opening interview, there’s no denying

the inspiration the experience gave to two young actors who would both go on to

make their mark!

* There are also two small parts for Christopher Lee and David McCallum, the former speaking as a German police officer and the latter pointing meaningfully in silence at the more code signal on the beach…

%20hill.JPG)

%20fox.JPG)

%20dress.JPG)

%20dress.JPG)

%20coffin.JPG)

+colour.png)