In the pre-screening Q&A with Bryony Dixon, composer Olga

Neuwirth mentioned that she had just heard Theresa May say that political leadership

wasn’t about the “easy task” but about “the right task” in response to the people’s

will. It’s a phrase that the Austrian felt chimed very much with the decision

by the Chancellor in this film’s fictitious country of Utopia when, responding

to the electorate’s constant blaming of the Jews for their every ill, he

decides to exile them all even against his better judgement.

Populism is nothing new and neither is religious

intolerance and this film and Hugo Bettauer’s book upon which it is based, are excruciatingly

prescient and so very relevant now as then and much in between. Shortly after

the film was released Bettauer was murdered by a former member of the Nazi

Party… a man who was released after spending just two years in a psychiatric hospital:

justice was poorly served in 1920s Austria and there was, of course, far, far

worse to come.

What began as a comedy satire thus ended up almost

immediately as tragedy and is now imbued with the unbearable weight of a history

with no sign of let up. Today, as the British government squabbled over Brexit

and our relationship with the European Union, a politics founded in defining

our commonality by rejecting “otherness” once again took its toll: it’s the

oldest trick in the book and it works a charm in extending human misery.

|

| The Chancellor |

Olga Neuwirth is an Avant Garde composer from Graz in

southern Austria, she is of Jewish heritage and has witnessed a rekindling of racial tensions throughout her

life in this mainly Slovanian area. The Austro-Hungarian Empire declined

throughout the Nineteenth Century leaving a power vacuum and messy local

conflicts one of which led to the assassination of Arch Duke Ferdinand.

She has worked on film before and developed an opera

based on David Lunch’s Inland Empire:

she knows her films and her music and felt a specific responsibility with this commission.

The result was uncompromising and nothing like we would normally hear for a

silent film score but she wanted to present musically the enduring socio-political

context this film already has.

Using a live orchestra of nine musicians and a

pre-recorded backing track she produced an unsettling score that was hand-in-glove

with the action on screen but which mixed jarring atonality with skilfully-twisted

lines designed to disrupt and disturb. At one point a drunken, disjointed Land

of Hope and Glory appears when some characters are in London, it was stretched

almost beyond recognition but gave a hint of how the other themes used

might sound to Austrians familiar with them: most of tonight’s audience didn’t have

that context.

|

| The people and their will |

She used songs which were popular at the time and tunes

which are contemporary symbols of the far right in Austria and always, wanted

to convey “the creepiness, the

uncertainty that everything can happen again… the past and the future are the

same; it can always happen again…” and the music plays a major part in the

connection.

The composer was already very familiar with the book and

the film and when the missing footage was rediscovered in a Paris flea market

in 2015… she was the natural choice even though she resisted at first and had

to be persuaded by the head of the Viennale

She believes that the book should be taught in Austrian

schools – Austria denied they were part of the Nazi programmes even until the

80’s – and feels it’s “already too late” to show the film given the rise of anti-Semitism

again in Austria. It’s a depressing point of view but it is her truth and this

is precisely why her score felt so angry; the more combative score I’ve ever

heard for a silent film, a call for action and attention beyond the prime

directive of accompanying this remarkable film.

This book is a satire but she didn’t feel that Bettauer

felt he was any way in danger – he was playing with forms, even he didn’t want

to recognise the seriousness… in the end it caught up with him as it has with

millions. So, quite logically, Neuwirth’s score is as close to a red flashing

light as you’ll get.

|

| A thoroughly disturbing poster from 1926 |

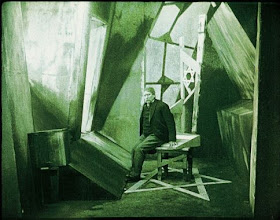

Now the film… Directed by H K Breslauer this is often

described as an Austrian expressionist film and yet, short of one great scene

when an antisemitic parliamentary representative Bernard (Hans Moser) is jailed

in a room full of twisted shadows and stars of David, it’s not going to pass

Lotte Eisner’s test. It is very expressive and directed with skill but it’s

tone – in sharp contrast to the score – is lighter given the expectation that the

scenes in the film would not come to pass (although in this respect the film is

more optimistic than the book).

Utopia is suffering from a devalued currency and post-war

economic strife and new chancellor, Dr. Schwerdtfeger (Eugen Neufeld) responds

to the ease as many voters blame Jews the hardship with their intelligence and

general association with finance and the “arts” (what reasons do you need?).

Gradually he accepts the unthinkable and passes a law banning Jews who must

leave the country by 25th December – and a Happy Christmas to you

too.

This impacts two lovers, Lotte (Anny Milety) who is the

daughter of one of the members of the assembly who approves the law, and a Jewish

artist Leo Strakosch (Johannes Riemann). She will never be able to see him as

strict laws define who is and who isn’t a Jew.

A rich American anti-Semite (goodness me…) helps give the

economy a lift and for a while, things improve for the Christians at least… but

soon Utopia suffers as other countries refuse to do business with them and

then, shock horror, their Yankee benefactor marries a rich Jewish girl.

At the same time the cultural life of Utopia suffers

without the creativity of the Jews, their plays and their music whilst café become

beer halls and a culturally-impoverished society becomes an intoxicated one.

As hyper-inflation kicks in – an all-too familiar

experience – jobs are hard to get and Utopia is heading for disaster. Luckily,

Leo, who has snuck back into the country disguised as a Frenchman, helps to

organise counter propaganda to get his people back.

There’s a sardonic laugh from the Brits as a title card

reveals they need a two-thirds “super-majority” to change to constitution in

order to allow the Jews back – imagine that Mr Cameron?! There’s just one man

in the way and Leo has a plan to deal with the troublesome Councillor Bernard…

City Without Jews

(1924) on its own merits is a well-made film with good comedy moments and

an excellent cast but in combination with Olga Neuwirth music it became something

else indeed. The process of watching silent film normally involves re-connection

with the sensibilities of the time and yet this performance did not allow that

and who am I to say that, this time at least, that wasn’t exactly the right

thing to do.

Whatever Albert Camus said about all art being an attempt

to reconnect with those things that first “moved you”, sometimes its purpose is

to agitate and to discomfort and to make you think. In which case job done.

A tip of the hat to the PHACE Ensemble as conducted by Nacho

de Paz who were fascinating to watch at work.

No comments:

Post a Comment