A sense of time when magic had a meaning... I wanted

to create a myth that was relevant to human experience.

Robert Wynne-Simmons

This film is set in a time before the potato famine, when

Ireland was a much more populous place and a happier one. Maybe that’s a

projection – a long standing one – but so much of the country becomes so hard

to view at this distance, especially when every one of you was called James

speaking personally, that it’s much clearer to imagine. So it was that a man

from Sussex, educated in Cambridge University, came to write and direct what

was the first independent Irish film made in half a century.

Robert Wynne-Simmons had previously tackled William Blake

and then the screenplay for the ultimate “folk horror” film, Blood on

Satan's Claw directed by Piers Haggard the man who really coined the

phrase. Wynne-Simmons had been working in Ireland and managed to, just about,

secure the funding for this labour of love which both answers the question

about what Irish cinema could be and highlights the riddle of why not more? It

is after two viewings, a film to bewitch and fall in love with, something the

director has been shocked by when he meets people who have been so deeply

affected by the tale.

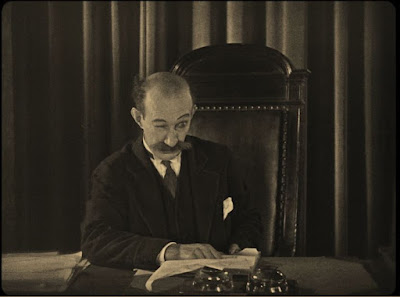

Cyril Cusack is the big name in the film and he was,

according to his director, very proud to have been in both this film and the

last independent Irish film, Guests of the Nation a silent film from

1934, directed by Denis Johnston, and including Barry Fitzgerald. The Irish

Film Board was set up in 1981 to boost the local industry, and Outcasts

certainly benefited from this backing along with Channel 4.

Cusack is of course wonderful; he was a master of nuanced

uncertainty and always conveyed mystery in his thoughts in ways utilized so

well by Michael Powell and Emeric Pressburger whose style of “magic realism”

runs through this film like the words Galway Bay running through a stick of seaside rock. But there’s a young performer called Mary Ryan who steals the film with

an almost mystical connection to the camera that you wouldn’t credit from

someone who was stage trained and with scant film experience.

Ryan plays Maura, a woman out of step with her fellow

villagers and even her family. She describes herself as a “mistake” and her

father’s regular if “well-intentioned” beatings are testament to her inability

to bend to his will. She is out of joint, seeing things her sisters don’t and

being relentlessly teased by the locals as we see at the film’s beginning when

two other girls throw her petticoat into the mud, forcing her to face the

indignity of wearing them. People are cruel but she has a strength in not

responding, almost as if she sees through their mundane games.

Like much else in the film, the explanation is left open

to the audience to interpret, as the BFI’s Vic Pratt says in his booklet essay,

ambiguity abounds; slippage of meaning is manifest... Maura’s sister Janey

(Bairbre Ní Chaoimh) is due to be married to Conor Farrell (Tom Jordan) who

has, it seems, put her in the family way. Their issue is discussed with local

civic leader Myles Keenan (Cyril Cusack) who arrives imperiously on horseback

with a shiver at the prospect of his old adversary Scarf Michael (Michael Lally),

who appears to him as a reflection in a pool. This apparition and the plaintive

fiddling is surely in his imagination or is it?

The wedding is agreed with old grudges put aside by

stubborn, grounded men, as much a part of the scenery as the buildings and even

the clothes feel rooted in the muddied earth, the dampness working its way up

the hems as the actors struggled against the elements. This is a “folk film”

before it’s a horror and the old behaviours and traditions are as mysterious as

any witchcraft. For the wedding party the youngsters run to the house and then

a band arrive carrying fiddles and dressed as Straw Men, Maura stares at these unknowable

men who ae welcomed in to serenade the party without question. That’s wyrd in

the old sense of the word and as frequently quoted by Dr Diane A Rodgers in her

excellent and informative commentary. Another level of the uncanny is added by

the faraway sounds of Scarf Michael’s fiddle… causing anxiety among the adults.

As the evening progresses the younger members of the

group wander off into the woods, leaving Maura alone as they pair off. She

waits in the eerie darkness with slivers of moonlight hinting at the uncertainty

of what’s beyond. Now she sees the figure of Michael, who appears to be there

and not there until he solidifies and approaches her. She joins him as he

exacts magical revenge on her tormentors as the drink and make love and she

enjoys the tables turned while it lasts.

The next morning, she wakes in a graveyard with Michael –

he often sleeps in such places “for the company” – only to find herself covered

in snow. It’s as if the world has changed but the reality was more prosaic as

the unexpected snow had slowed production even as it allowed for this deft

stroke from the director. Soon though the locals are turning on Maura and blaming

her for blighted potatoes and consorting with the unnatural Michael. Will he

save her, and, even as he holds back from revealing the truth of what he knows

and she longs to find out, we wonder what will become of her…

Wynne-Simmons’ team clearly laboured with a love of the

subject and in his essay in the booklet he is quick to credit them feeling

privileged by the way in which both cast and crew responded to the creation of

this ‘other world’.

|

| People and the earth |

Séamus Corcoran, the lighting cameraman, had a deep

understanding of the countryside and of the light in people’s eyes. Consolata

Boyle created costumes that seemed to grow out of the ground itself. Stephen

Cooney’s beautiful music was enhanced by dark didgeridoos from his native

Australia, emphasising how the human subconscious unites all the world.

As the Englishman telling this most resonant of Irish folk tales there’s a touch of Bruce Chatwin’s belief in the universality of folkloric “songlines” which echo down from the past through our generations be they describing Cooney’s outback, the Pilgrim’s Way to Canterbury or the invisible ties that bind in Isle of Kiloran. Maura experiences her landscape as a revelation and one that she will have to discover how to share with her family and others outside of her higher consciousness.

Extras are magical:

·

New 2K restoration by the Irish Film Institute

·

Newly commissioned audio commentary by Dr Diane

A Rodgers

·

Writing Folk Tales (2024, 9 mins): a newly

recorded interview with director Robert Wynne-Simmons

·

The Fugitive (1962, 31 mins): Robert

Wynne-Simmons’ first film with an outsider at its heart is this dark tale of

violence, guilt and retribution shot on 8mm film amidst Mods and Rockers

violence on the backstreets of ‘60s Brighton

·

The Outcasts in Pictures (2024, 15 mins):

a gallery of stills from the film with audio commentary by director Robert

Wynne-Simmons

·

The Wanderings of Ulick Joyce (1968, 5

mins): this distinctive animated short by Gillian Lacey was inspired by Irish

folk tales, and was made with the assistance of the BFI Production Board

With the first pressing only, there’s a very

impressive booklet including director’s statement, new writing on the film by

the BFI’s Vic Pratt, an archive essay by Dr Diane A Rodgers and recollections

of The Fugitive by Robert Wynne-Simmons.

It’s out now, so get your order in quickly – this is a

film you’ll want to watch over and again, a puzzle open to interpretation and

one that will touch each of us in different ways. A wonder.

.JPG)

%20paint.JPG)

.JPG)

%202.JPG)

%20total%20war.JPG)

%20Ice%20Cream%20Cohen.JPG)

.JPG)

.JPG)

%20gang.JPG)

%202.JPG)

%202.JPG)

.JPG)

%202.JPG)

.JPG)

.JPG)

%20header.JPG)

.jpg)

.JPG)